The One Minute Learner

Miriam Hoffman, MD, and Molly Cohen-Osher, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Boston University

Student and teacher expectations drive the activities and anticipated outcomes in any teaching/learning environment. Many medical educators have seen the results of mismatched student-teacher expectations: students feel that they are not being told what they need to do, teachers feel students are not listening or anticipating, students complain that they are being evaluated unfairly, and others. Mismatches in what either teacher or learner expects and what actually happens may set up teaching encounters to falter. For example, if a preceptor expects a student to be at a certain level of clinical skill, but the student is in fact not at that level, the responsibilities and performance expectations for that student will be incorrect. This can lead to poorer quality teaching and learning, frustration, student anxiety, and problems with evaluation.

Additionally, having clearly defined and articulated goals is critical to the success of a teaching encounter—be it for precepting one patient, for supervising a clinical session, or for an entire block rotation. Learners are increasingly encouraged to create their own learning goals in addition to the goals provided by the course/rotation. Creating learning goals helps a student focus his/her learning, and discussing these goals with a faculty member allows them to tailor the student’s learning experiences. However, these goals, both from the course/rotation or created by the individual learner, are frequently forgotten about and not discussed with the clinical teacher.

Further, a large challenge to medical student education, particularly in family medicine, is the wide array of clinical settings and teachers where and with whom our students work. Not all of these teachers remember to discuss goals and expectations with their learners. Additionally, those who do intend to have that discussion do not always have the time. Further, and perhaps most importantly, many preceptors do not realize the critical importance of discussing goals and expectations to the success of clinical learning and so therefore do not routinely do this.

To alleviate these problems, we have developed the One Minute Learner. The One Minute Learner is an easy-to-use and efficient tool that promotes and structures a conversation about goals and expectations for clinical teaching sessions. Either faculty or student can initiate the tool. It enables and structures a quick and simple conversation that allows students and teachers to be “on the same page,” which leads to a satisfying and productive clinical teaching session.

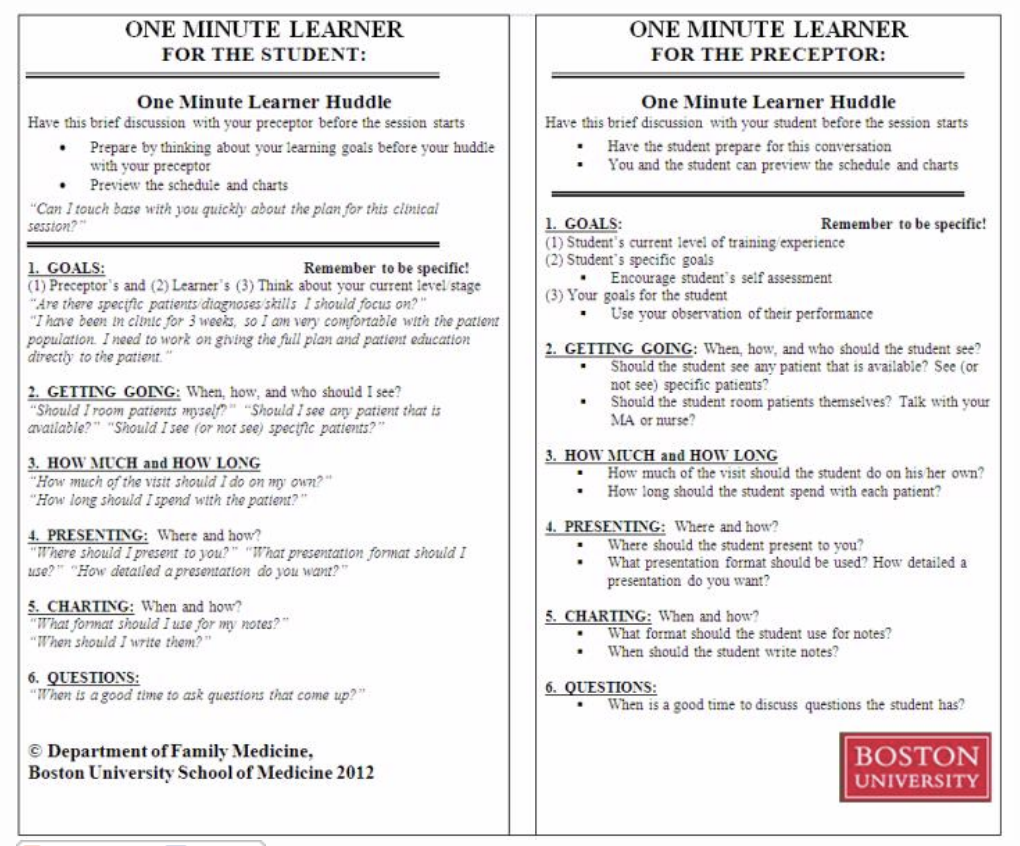

Below, the student and faculty versions of the One Minute Learner are described. The six components are the same in both versions but are presented to the perspective of the student or faculty, respectively. The faculty pocket card includes both the faculty and student versions on either side of a pocket card. The student version includes examples of actual words and language that the student can use for each component (in quotes and italicized).

There are six components to the One Minute Learner:

1. Goals

2. Getting Going

3. How Much and How Long

4. Presenting

5. Charting

6. Questions

These six steps are discussed during the One Minute Learner Huddle, which is a brief conversation between the student and faculty prior to a clinical session. Students and faculty are encouraged to prepare for the huddle. Students are encouraged to think about their learning goals both for the rotation and for the specific clinical session, preview the day’s schedule, and identify appropriate patients. Faculty are encouraged to preview patients for the clinical session with the student’s learning needs/goals in mind.

1. Goals

The discussion about goals has three components: what is the student’s current level of training/prior experiences, what are the student’s specific learning goals, and what goals does the faculty have for the student?

We encourage students to base their learning goals on a self assessment they complete in the beginning of the clerkship. We discuss with students that they will have short-term goals (ie, for a clinical session) and longer term goals (ie, for the entire clerkship). We encourage the preceptors to consider the student’s own goals and self assessment and their prior observation of the student when discussing goals they may have for the student.

2. Getting Going

When and how should the student start seeing patients? For example, which patients should the student see (or not see)? Who should room the patients?

3. How Much and How Long

What should the student do in the room with the patient? For example, how much of the visit should the student do on his/her own? How long should the student spend with each patient?

4. Presenting

Where and how should the student present? For example, where should the student present (in front of the patient, outside of the room, etc)? What format should they use for presenting? How detailed should the presentation be?

5. Charting

When and how should the student write notes? For example, what format should the student use for his/her notes? When should the student write the notes?

6. Questions

When should the student ask questions that they have? For example, should the student wait until the end of the session? Should they ask questions as they come up?

When and How to Use the One Minute Learner

At times, most or all of the components of the One Minute Learner will be used, and at other times, only certain parts will be discussed. For example, at the beginning of a rotation, a preceptor and student may use all six components, whereas a few weeks into a rotation, a preceptor and student might only discuss the goals section. At a clinical site where the student works with many different preceptors, the primary preceptor might review all six components at the beginning of the rotation, and other preceptors might use two to four components before any given clinical session with the student; for example, reviewing the particular faculty’s preferences for presenting and charting.

The One Minute Learner is specialty neutral and clinical setting neutral. It can be used in inpatient and outpatient settings, and in any clinical field. Additionally, it can be used with both medical students and residents. It does not take long to discuss, does not need to be used at every clinical session, and at times only certain components will be needed.

Using the One Minute Learner With Family Medicine Clerkship Students

We have used the One Minute Learner in our Family Medicine Clerkship and have presented it to our students as a tool for them to use to initiate these conversations. We chose to do it this way because this provides the additional lesson of the importance of being an empowered, proactive learner. Being able to articulate one’s own learning needs and goals and ask about expectations is a critical skill and one that many students are not used to as they enter the clinical years of medical school. This simple tool empowers the students—giving them the structure, tools, and even the language—to be proactive in articulating and discussing both their learning needs and what is expected of them. This tool has been well received among our students and is routinely being used. We have seen a positive impact on student experience at the clinical site.

The One Minute Learner as a Faculty Development Tool

The One Minute Learner is also a powerful faculty development tool that we have presented to our own faculty and at national conferences. It prompts faculty to routinely set goals and expectations, which is of vital importance to the learning environment and learning outcomes. It is written in a way that requires both faculty and student input, so it facilitates a shared approach to learning and student-directed goal setting. Training our students in using the One Minute Learner, and then sending them to their preceptors with the empowerment, structure, and language to initiate these discussions is also a way to provide on-site and real-time faculty development for our preceptors.