Family Medicine Residents’ SBIRT (Screening, Brief Intervention, Referral for Treatment): The Patient’s Perception

Brenda Moore, DO; Alicia Kowalchuk, DO; Vicki Waters, MS, PA-C; Larry Laufman, EdD; Ygnacio Lopez III, MS; Elizabeth H. Shilling, PhD; Jane Corboy, MD; Fareed Khan, MD; James Bray, PhD, Baylor College of Medicine

Substance use is a major contributor to primary care visits for both adolescents and adults. While many adult and adolescent users of alcohol and drugs are not seeking treatment, they represent an opportunity for early intervention by screening.1 Screening, followed by a Brief Intervention (SBI) has been shown to make a difference in long-term change.1-3 Use of Screening, Brief Intervention, Referral for Treatment (SBIRT) in primary care may be the greatest opportunity to assess and affect change of risky behavior in patients not currently seeking help and not yet ready for treatment.3 Family physicians, who see patients of all ages, should be trained in SBIRT techniques.

In the Baylor family medicine residency training, all interns go through a half-day SBIRT training session, where residents are taught validated screening tools, including the brief three-question screening tool (Do you smoke or use other tobacco products? When was the last time you had more than four drinks in one day? How many times in the past year have you used an illegal drug or used a prescription medication for non-medical reasons?), the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST), the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT), and the CRAFFT (a drug and alcohol screening tool for adolescents). Residents spend time practicing the screening and brief intervention techniques with trained SBIRT observers. Didactic sessions include discussion on the uses and importance of brief intervention and the various treatment centers available. Badge cards with the brief three-question screening, a readiness for change ruler, and score implications for the CRAFFT, DAST, and AUDIT are given. Additional follow-up 1-hour didactic sessions are given approximately once per quarter during the core didactic sessions. These emphasize key SBIRT concepts and include additional practice time.

In addition, every spring, two residents from each residency program at Baylor are chosen to go through Resident Champion Training, a 3-day intensive SBIRT training with more in-depth practicing. The Champion training expands on the brief intervention section of SBIRT by focusing on key Motivational Interviewing (MI) skills and also includes additional sessions on adolescent SBIRT, co-occurring disorders, pain and addiction, impaired professionals, and medication management of addictive disorders as well as teaching the next generation of residents—stressing the importance of mentoring and demonstrating SBIRT skills. All residents that have gone through training are encouraged to discuss what has worked for them within the larger group of residents.

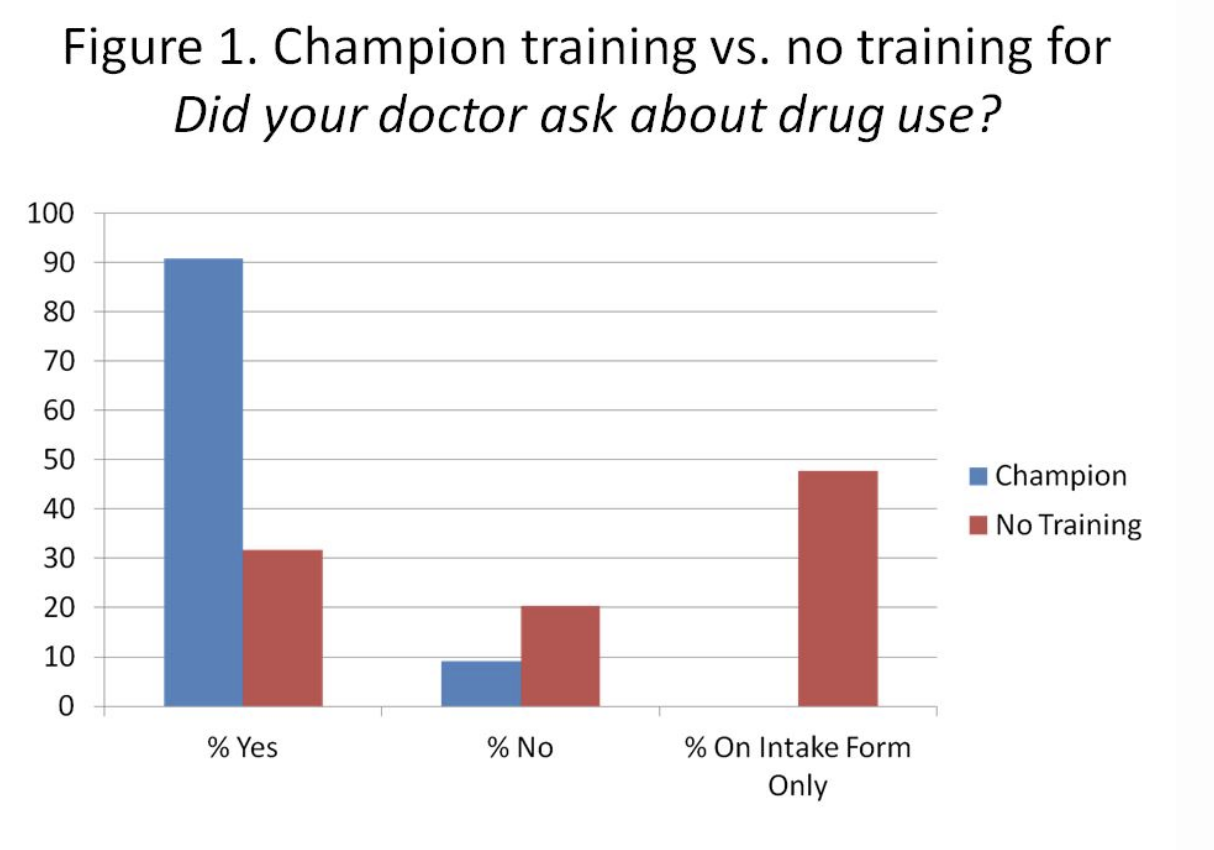

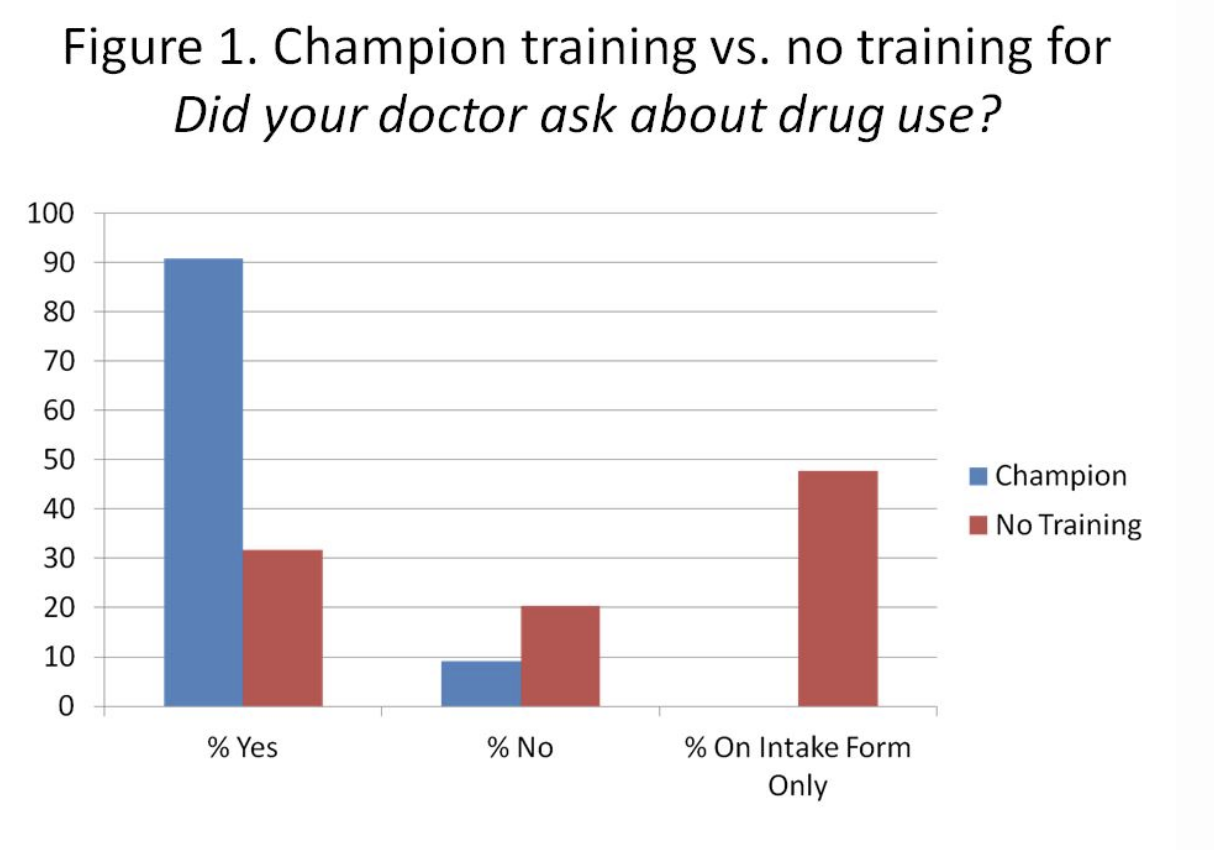

We performed a survey-based pilot cohort study to assess patients’ perceptions of providers with SBIRT training as compared to providers without training. The survey asked about initiation of discussions about tobacco, alcohol, and drugs and how comfortable the patient would be in discussing these topics. There was a significant difference in patient perceptions of Champion SBIRT-trained providers compared to non-trained providers regarding the frequency of provider-initiated discussions of patient tobacco and drug use. The patients of SBIRT Champions perceived their provider initiated these discussions more often than the patients of non-SBIRT trained providers (tobacco, 40% more; drugs, 60% more). There was not a difference in patient perceptions of how comfortable they would be in communicating with, teaming with, and collaborating with their provider regarding a potential substance use issue.

The Baylor College of Medicine InSight SBIRT Residency Training Program facilitators teach SBIRT techniques to five different programs, one of which is family medicine. According to the surveys collected February 2011 through March 2013, more than 8,500 patients have been screened by 26 family medicine residents, and through the SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) grant, the program continues to grow. One barrier is how to fund the project once the grant is completed, overcome in part by teaching the champions to teach the program to future residents. Another barrier is involving our attending providers in the education, so that frequent reinforcement could be consistent. While this study suggests SBIRT training is making a difference, we will need to expand the study to tease out finer details.

References

- Mitchell SG, Gryczynski J, O’Grady KE, Schwartz RP. SBIRT for adolescent drug and alcohol use: current status and future directions. J Subst Abuse Treat 2013 May-Jun;44(5):463-72. http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxyhost.library.tmc.edu/science/article/pii/S0740547212004382. Accessed March 26, 2013.

- The Insight Project Research Group. SBIRT outcomes in Houston: final report on Insight, a hospital district-based program for patients at risk for alcohol or drug use problems. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2009 Aug;33(8):1374-81.

- Madras BK, Compton WM, Avula D, Stegbauer T, Stein JB, Clark HW. Screening, brief interventions, referral to treatment (SBIRT) for illicit drug and alcohol use at multiple healthcare sites: comparison at intake and 6 months later. Drug Alcohol Depend 2009 Jan 1;99(1-3):280-95.