Stimulating Research Capacity in Family Medicine Residencies by Engaging Programs in Both Research and Quality Improvement

Allison Cole, MD, MPH, Ardis Davis, MSW, Gina A. Keppel, MPH, University of Washington; Janelle Guirguis-Blake, MD, Tacoma Family Medicine Residency, Tacoma, WA; Rex Force, Pharm D, Family Medicine Clinical Research Center, Idaho State University; Al Berg, MD, Laura-Mae Baldwin, MD, MPH, University of Washington

Building research capacity in family medicine residency programs is a critical element to improving the quality of primary care. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education now requires residents and faculty to demonstrate evidence of active scholarship and research.1 However, scholarship activity in family medicine residency programs remains low, especially in community-based programs.2,3 Family medicine residency programs seek ways to integrate scholarly work within the context of their clinical and educational missions.4 Our experiences with the WWAMI (Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho) Family Medicine Residency Network (FMRN) found that intersecting research and quality improvement (QI) in a network of family medicine residency programs helped develop a practice-based research network (PBRN) and increased these residency programs’ research capacity and productivity.

The FMRN includes 20 family medicine residency programs across five states.5 In 2006, the FMRN program directors identified building research capacity as a strategic direction. A Steering Committee of University of Washington family medicine researchers and FMRN program directors convened to develop and engage FMRN practices in a pilot research project. The objectives of this pilot were (1) improve quality of care in FMRN practices, (2) contribute to the primary care knowledge base, (3) engage FMRN residents in the research process, and (4) increase research capacity in FMRN practices.

The Steering Committee chose a project that included a QI component along with research. The project examined use of contraception and informed consent among women of childbearing age who were prescribed medications with potential adverse fetal effects. Participating sites developed a QI intervention and chart abstraction for outcomes before and after implementation of the QI interventions. Thirteen programs initiated the study, and seven programs completed the study. Barriers to completion included difficulties with the IRB process and turnover of the site research champion. Study completion led to faculty authorship (seven faculty, one chief resident) of two peer-reviewed manuscripts and at least three presentations at national meetings from all of the seven participating programs.

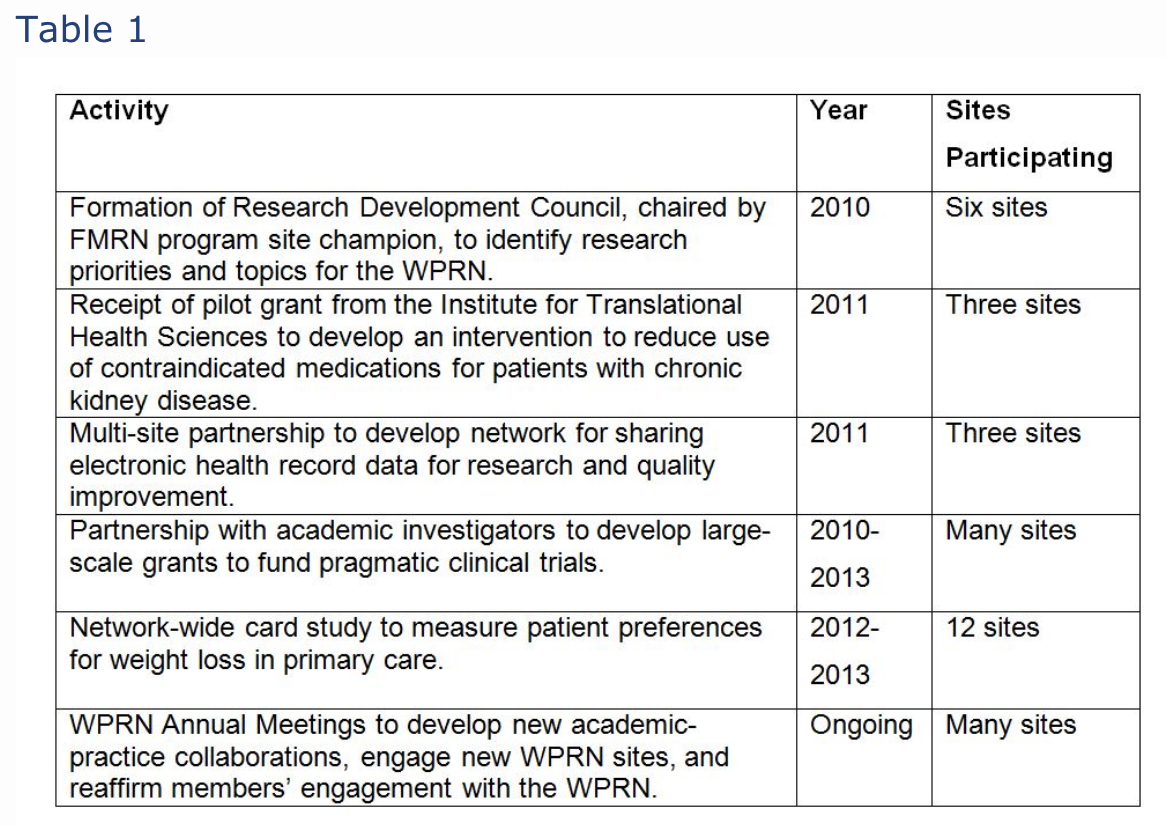

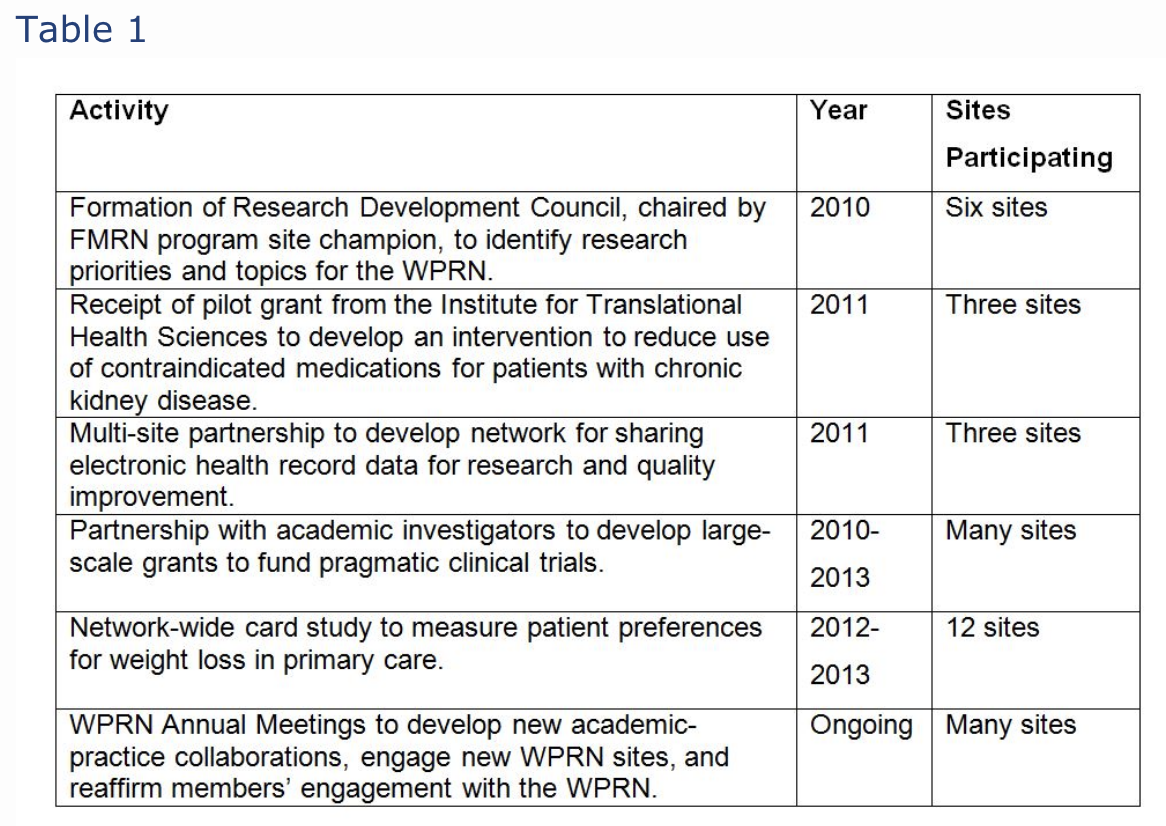

Development and implementation of this first QI study led to increased interest in ongoing research and scholarship. In 2011, six of the sites completing the project, along with seven other FMRN practice clinic sites, formed the Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho region Practice and Research Network (WPRN). As of 2014, 17 residency programs joined the WPRN. Residency program directors reported their primary motivations for participation in the WPRN included both undertaking quality improvement programs at their clinical sites and the potential to increase scholarship opportunities for residents and faculty within their programs. Table 1 outlines the research activities of the FMRN programs that participated in the initial pilot study and that remain active members of the WPRN.

The pilot project and its emphasis on research linked to QI helped meet the residency programs’ goals of increased scholarship and research capacity. Our experience supports findings that combining QI with research is a key motivator for PBRN participation.4,5 Commonly identified barriers to research participation for community residency programs include lack of research infrastructure, protected time, and adequate funding, as well as IRB hurdles, and PBRNs may be an important way to address these barriers.5 The WPRN provides ongoing technical support, expertise, and mentorship to faculty and residents in the FMRN, thereby creating an enduring partnership. Our experience suggests that collaboration between PBRNs and family medicine residency programs can increase research opportunities in family medicine residency programs while simultaneously improving quality of care.

References

1. Education ACfGM. Common Program Requirements. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs2013.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2013.

2. Crawford P, Seehusen D. Scholarly activity in family medicine residency programs: a national survey. Fam Med 2011;43(5):311-7.

3. Young RA, DeHaven MJ, Passmore C, Baumer JG, Smith KV. Research funding and mentoring in family medicine residencies. Fam Med 2007;39(6):410-8.

4. Young RA, Dehaven MJ, Passmore C, Baumer JG. Research participation, protected time, and research output by family physicians in family medicine residencies. Fam Med 2006;38(5):341-8.

5. Force RW, Keppel GA, Guirguis-Blake J, et al. Contraceptive methods and informed consent among women receiving medications with potential for adverse fetal effects: a Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, Idaho (WWAMI) region study. J Am Board Fam Med 2012;25(5):661-8.

Financial Support

This publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR000423. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, University of Washington Family Medicine Residency Network,or University of Washington Department of Family Medicine.