Creative Reflections on the Coronavirus Pandemic: A Virtual Exercise to Promote Learning and Well-Being

by Shannon Stark Taylor, PhD and Joel Amidon, MD, Prisma Health Family Medicine Residency, Greenville, SC

Background

The coronavirus pandemic presents distinct challenges to residency programs attempting to promote resident well-being and connectedness by hampering the ability to gather physically. Despite this, it also offers opportunities for learning, given the unique nature of this event in public health history. We describe here a virtual creative reflection exercise delivered with the goals of promoting resident learning and well-being.

Reflection has been posited as a means for learning in medical education by promoting the development of professional expertise and allowing for the exploration of emotions. Novel experiences like the pandemic offer a critical opportunity for reflection in action, allowing for modification of practice in real time,1 as well as the integration of mental models that can be deployed to respond to new, complex, and poorly defined future situations.2 Both are defining features of professional expertise. Exploring emotions, both one’s own and others’, 3 is critical for learners during this stressful and potentially traumatic time. Reflection has been thought to increase provider well-being by promoting self-healing through processing difficult experiences and emotions, reducing isolation, and restoring a sense of community.4 Indeed, systematic self-reflection about one’s response to a stressor has been theorized as key to promoting resilience.5

We designed this exercise to provide a structured venue to discuss team members’ experiences, relate to one another, normalize experiences, provide support, and foster connectedness while physically distanced. Although residents in our program engage in monthly narrative medicine reflective sessions, this was the first time they explored other modes of creative expression.

Intervention

This virtual creative reflection exercise was administered in a video call didactic session. Residents were informed of the goals of the session and the reflection prompt (Figure 1) 2 days prior, allowing extra time for those wanting to start early or gather desired materials. At the beginning of the session, the prompt was reviewed, and residents viewed a faculty member’s example reflection. Residents signed off the video call and individually completed a reflection in 45 minutes. Next, participants logged onto new video calls in three smaller groups (six to eight residents distributed evenly by class [19 residents total], one faculty/staff leader). Each group member shared his/her reflection with the group. Leaders prompted for additional thoughts/reflections, and other group members provided feedback. Leaders then facilitated a more general discussion about the group’s experiences during the pandemic. Small group discussions lasted 45 minutes to 1 hour; the entire session lasted 1.5– 1.75 hours. An anonymous survey about participants’ experiences was distributed 1 week after the session via email.

Results

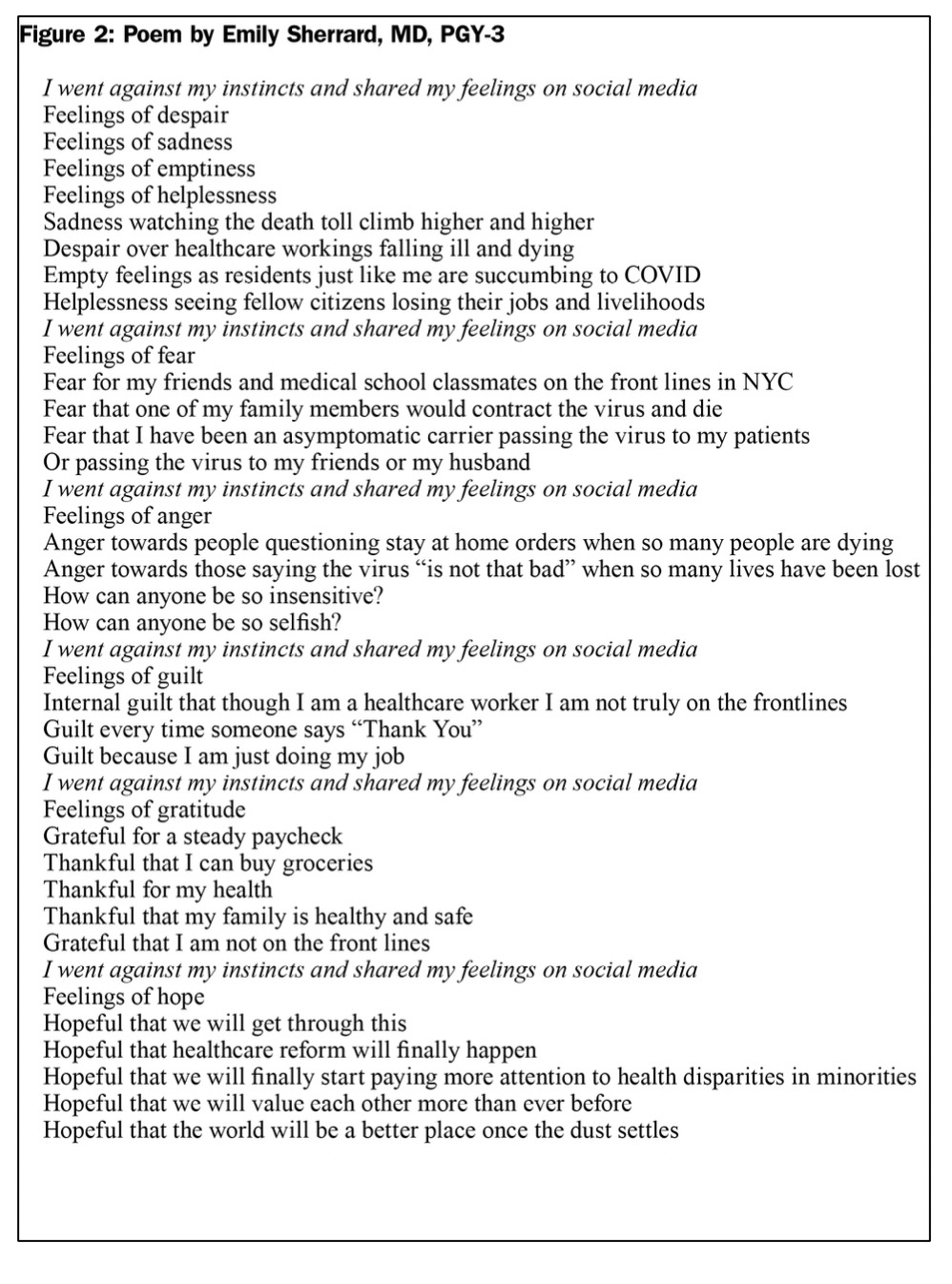

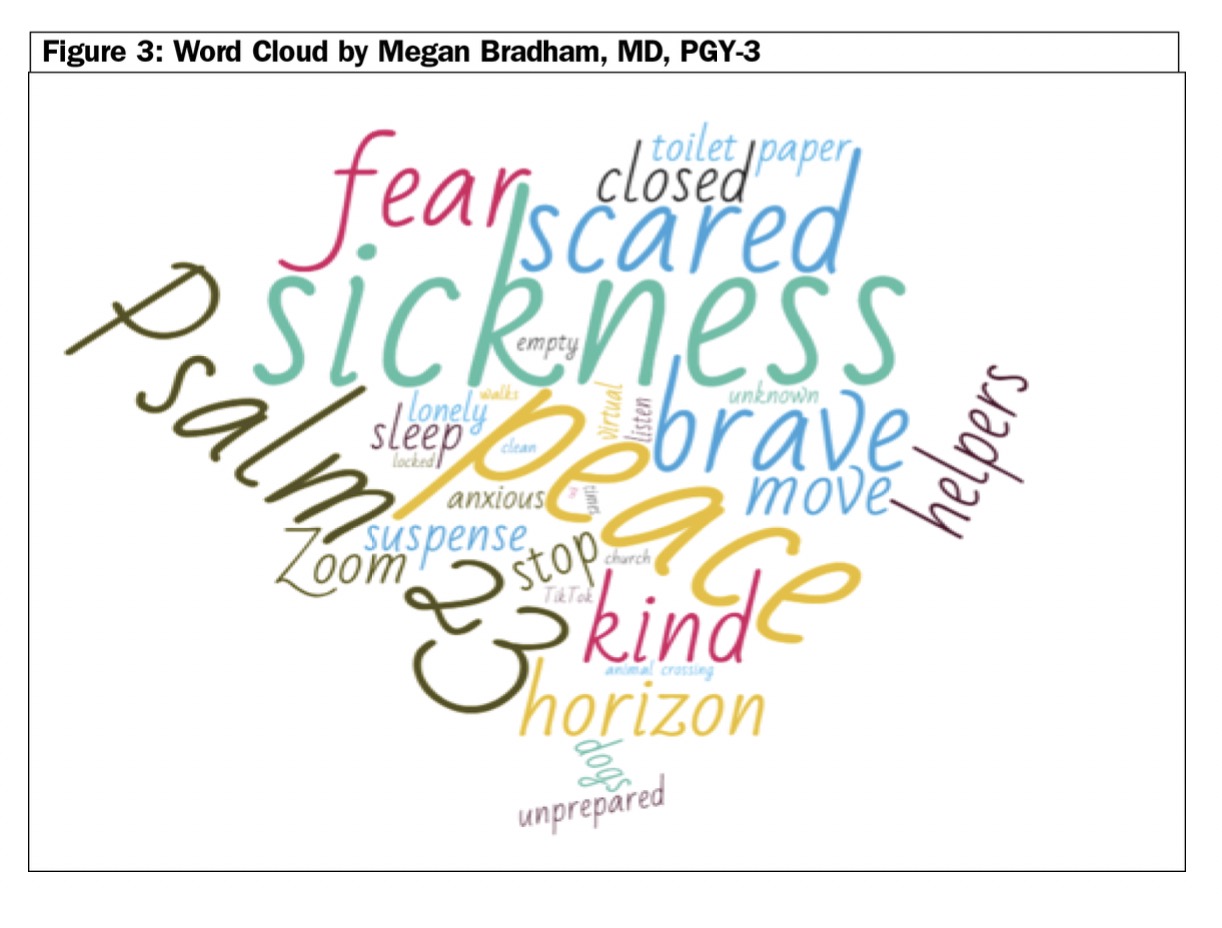

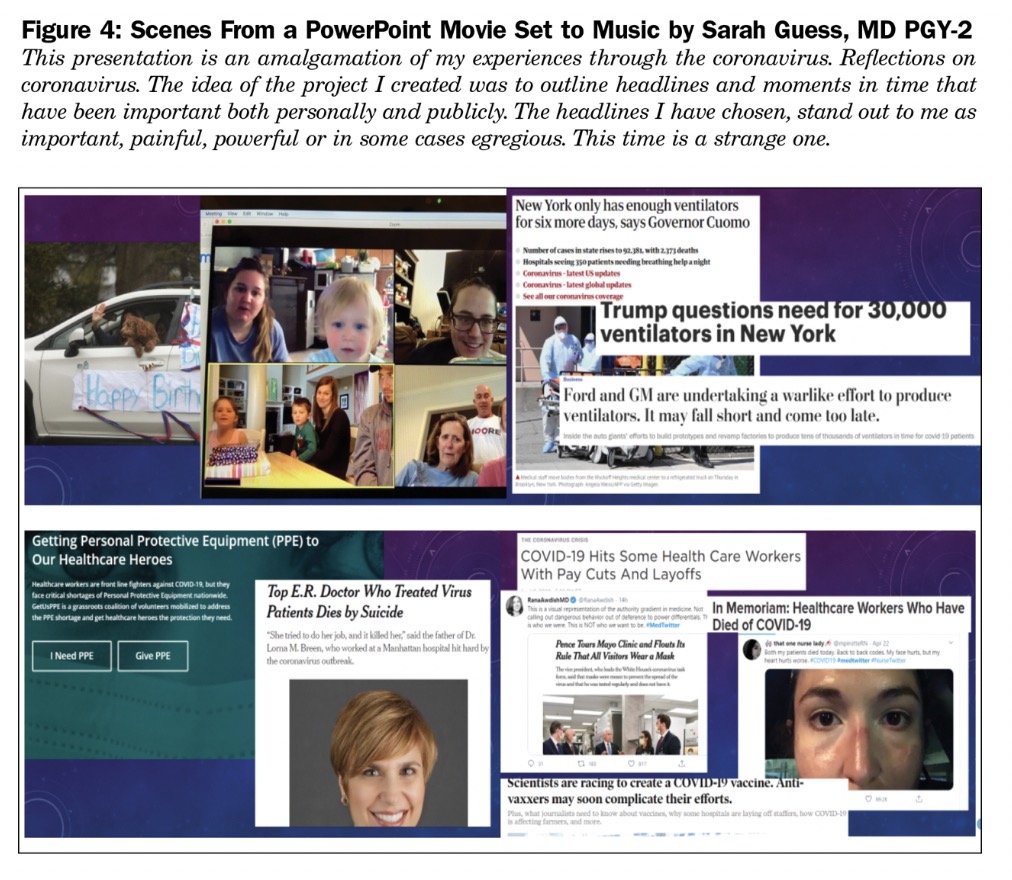

All small group attendees completed the reflection and shared it with their group. They created a wide range of creative reflections including photographs, videos via PowerPoint and YouTube, poetry, visual presentations of words or photos, prose, and even a skit (Figures 2-4). Some participants did not include personal thoughts or emotions (focusing more on reporting actual experiences as a resident/citizen during this time), although many did offer this information verbally when prompted. The reflections fostered rich discussion about common experiences during the pandemic. For example, many related to the experience of feeling guilt when others told them “thank you” because they did not feel truly on the frontlines. Residents provided a lot of verbal support to one another as they were less able to express nonverbal support. Breaking into smaller groups decreased the intimidation factor of disclosure to a large virtual group and saved time, offering the opportunity for more in-depth discussion in each group. Results from a survey administered 1 week after the exercise are presented in Table 1. Those who completed the postintervention survey noted generally positive experiences completing and discussing reflections, many noting that the exercise helped them gain insights into their experiences.

Table 1: Survey Results

|

Question |

M (SD) N = 9 (2 faculty, 7 residents), 1-5 Scale 1= Strongly Disagree, 5= Strongly Agree |

|

I enjoyed the process of creative reflection. |

3.78 (1.48) |

|

Reflection provided me with new insights about my experiences living through the coronavirus pandemic. |

3.89 (1.05) |

|

I appreciated the opportunity to share my reflection and hear others' reflections. |

3.78 (1.30) |

|

Hearing others' reflections helped me gain insights into my own experiences. |

4.11 (1.05) |

|

I appreciated having the opportunity to talk about what the coronavirus experience has been like. |

3.78 (1.20) |

|

Qualitative feedback |

|

|

“It was a great exercise, I used to write a lot and haven't since residency so this was a good experience.” |

|

|

“I was impressed and humbled by the amount of creativity and emotion that went into this activity for both faculty and residents.” |

|

Conclusions

We found this creative reflection exercise feasible to implement virtually. In general, residents appreciated the opportunity to reflect, be creative, and share. This exercise may be useful to other programs who aim to promote resident well-being through reflection, connection, and support during the coronavirus pandemic.

References

- Schön DA.The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1983.

- Sandars J. The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 44. Med Teach. 2009;31(8):685-695. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590903050374

- Hargreaves K. Reflection in medical education. J Univ Teach Learn Pract. 2016;13(2):6.

- Shapiro J, Kasman D, Shafer A. Words and wards: a model of reflective writing and its uses in medical education. J Med Humanit. 2006;27(4):231-244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-006-9020-y

- Crane MF, Searle BJ, Kangas M, Nwiran Y. How resilience is strengthened by exposure to stressors: the systematic self-reflection model of resilience strengthening. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2019;32(1):1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2018.1506640