Other Publications

Education Columns

A Novel Approach to Residency Sick Call

By P. Elainee Poling, MD; Margaret Dobson, MD; Anna McEvoy, MD; Leigh Morrison, MD, Department of Family Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MIDuring residency training, residents require unplanned time off for situations like illness, fatigue, or family emergency, to name a few. A recent survey of residents shows that presenteeism (working while ill) is prevalent, with over half of residents reporting working while sick at least once in the previous year.1 Another study showed that one of the most reported reasons for residents working while sick was an obligation to colleagues.2 The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) acknowledges that self-care and support of colleagues through non-reciprocal coverage are important in creating an ideal culture of professionalism, a core competency in residency.3 Furthermore, ACGME requirements state that programs must ensure coverage for patient care when unexpected scenarios arise3 and the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) recommends that medical students ask about sick call when they interview for residency.4 Having an inadequate coverage system can perpetuate presenteeism, and result in missed educational opportunities when residents are pulled from planned training experiences to provide coverage for their absent colleagues. Yet, residency sick call is virtually unaddressed in the medical literature.

Residents at our program expressed increased stress regarding sick call frequency and the coverage process. In response, we developed a novel sick call curriculum aimed to reduce barriers to calling for coverage while minimizing interference with residency education, patient care, and resident wellness. We named this coverage system the Flex Teacher curriculum. The name is descriptive of the curriculum, in which clinical duties are not assigned and residents spend time on educational, administrative, or scholarly work. Additionally, the curriculum includes a peer-teaching component in which residents develop brief clinical talks to present to their peers on the inpatient wards. While on this rotation, the assigned residents are the first point of contact for providing coverage. At our institution, two residents (one second year and one third year) are on the rotation at any given time, and residents are assigned year-round. If more than two residents are needed for coverage simultaneously, regular rotations might still face interruptions, however the frequency of this is much lower after implementation of the Flex Teacher Curriculum.

The curriculum is unique as it assigns sick call without other clinical duties. Therefore, residents do not miss planned clinical experiences when called for coverage. We were able to accomplish this while transitioning our residency program from a monthly calendar (12 rotations per year) to a four-week calendar (13 rotations per year), as well as utilizing some elective time. It is most feasible within a large academic residency program, with more residents to divide call coverage, however, is adaptable for residencies of any size. The structure lends itself to residents working as a team, rather than pushing through illness, personal stress, or family crises for fear of negatively impacting peers by calling for coverage.

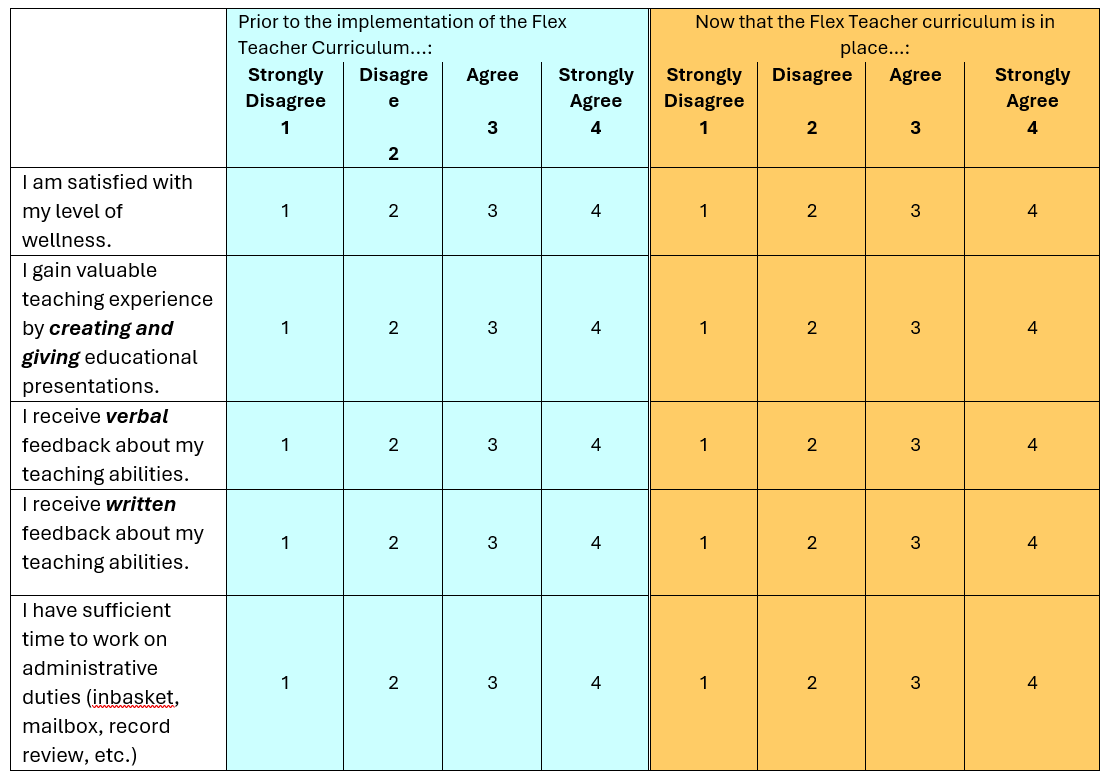

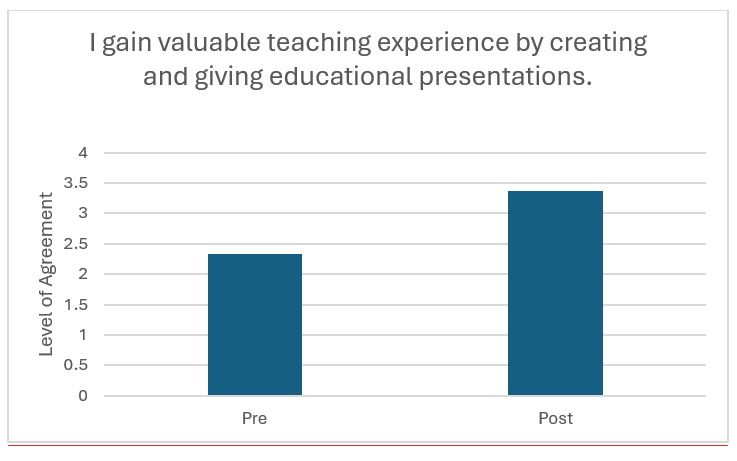

In reviewing pre- and post-intervention survey data (see Table 1 for abridged survey) and tracking schedule changes, the flexible structure minimized disruption to core rotations, while prioritizing the residents’ request for increased time for educational development, administrative work, and asynchronous patient care. Overall, the residents found the peer-teaching program valuable (Figure 1), both as teachers and learners, and reported receiving increased feedback on their teaching skills. However, these changes did not shift their overall perception of wellness. Despite equal time on the rotation, the residents cited call burden inequality as a limitation, and the unplanned nature of absences makes this difficult to control.

Table 1

Figure 1

Being on sick call and requesting coverage continues to be stressful, and it is still unclear what factors would mitigate stress and support comfort and acceptance in calling for coverage. We hope that continued investigation of peer-coverage curricula will further elucidate how a sick call system can best support a culture of wellness and professionalism. While this important work is being done, we hope that other residencies will consider our novel approach to residency sick call and consider utilizing an adapted form of the Flex Teacher curriculum to structure sick call while improving time for formalized peer teaching and individualized educational development.

References

- Jena AB, Baldwin DC, Daugherty SR, Meltzer DO, Arora VM. Presenteeism Among Resident Physicians. JAMA. 2010;304(11):1166-1168. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1315

- Jena AB, Meltzer DO, Press VG, Arora VM. Why Physicians Work When Sick. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2012;172(14):1107-1108. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1998

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. July, 2023. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/120_familymedicine_2023.pdf

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Insight From Residents on What to Ask During Residency Interviews. Students & Residents. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://students-residents.aamc.org/interviewing-residency-positions/insight-residents-what-ask-during-residency-interviews