Other Publications

Education Columns

Understanding the Perceptions of Geriatric Medical Educators Around Teaching Clinical Reasoning to Medical Learners

By Julie N. Thai, MD, MPH, Section of Geriatric Medicine, Division of Primary Care and Population Health, Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine

Background

Older adult patients often present as diagnostic challenges for several reasons, including communication barriers between clinicians and patients, complex comorbidities, and clinician biases that may affect quality of care.¹,² This population is particularly vulnerable to medical errors, especially those involving medication use.³

In addition, current literature indicates that more than 10% of cases of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, dementia, Parkinson disease, cerebrovascular accident/transient ischemic attack, and acute myocardial infarction are misdiagnosed (either overdiagnosed or underdiagnosed) among patients aged 65 years or older.⁴ The proportion of older adults in the United States is projected to increase to approximately 21.6% by 2030.⁵ Despite this demographic shift, there remains limited expertise on how best to address and overcome diagnostic challenges in this population.

Clinical reasoning—the process of gathering and interpreting information, formulating differential diagnoses, and determining diagnostic probabilities—is a complex skill taught through both theoretical and experiential learning.⁶ However, it remains unclear how medical learners are taught clinical reasoning in ways that promote diagnostic excellence when caring for older adults.⁷

Methods

A national cross-sectional survey was conducted to assess the perceptions of geriatric medical educators regarding the teaching of clinical reasoning skills to trainees. Eligible participants were geriatric medical educators in the United States who interacted with medical learners in any capacity.

Participants were recruited from 2 sources: (1) the directory of geriatric medicine fellowship program directors (PDs) obtained through the American Medical Association FREIDA database (N = 76) and (2) the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) member discussion forum (AGS membership >6000; the number of active forum users eligible for inclusion is unknown). PDs were included as they represent known geriatric medical educators.

Recruitment emails were sent to PDs, and study information was posted on the AGS forum. Both communications contained a link to the survey, which was administered via Qualtrics. Reminder emails and posts were distributed 7 days after the initial outreach. Descriptive statistics and frequency analyses were performed.

This study was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board. Funding was provided through the Age-Friendly Fellowship of the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine, in collaboration with the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the John A. Hartford Foundation.

Results

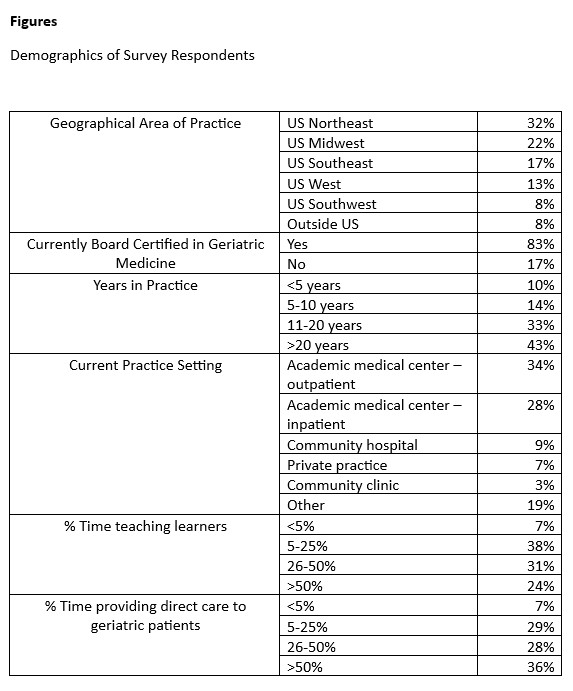

A total of 60 respondents participated, all of whom self-identified as geriatric medical educators. Most were physicians board certified in geriatric medicine and practicing in academic medical centers.

- Perceptions of clinical reasoning training: 65% agreed that explicit training in clinical reasoning can reduce medical errors and improve diagnostic accuracy.

- Training experience: 37% reported having received formal instruction on teaching clinical reasoning; 41% reported not knowing where to obtain such training.

- Training interest: 78% expressed interest in receiving additional training.

- Reported barriers: Lack of teaching time and lack of formal training in clinical reasoning concepts were identified as primary barriers.

The main limitation of this study was the small sample size. However, the aim was exploratory—to gather preliminary insights into the needs and perspectives of geriatric medical educators regarding clinical reasoning instruction.

Discussion

Findings from this study align with prior research demonstrating that medical educators have called for structured, formalized training in teaching clinical reasoning.⁸⁻⁹ A recent national needs assessment across multiple disciplines similarly found that while clerkship directors recognized the importance of clinical reasoning instruction, they were constrained by limited curricular time.¹⁰

Despite the small sample, the results of this study have important implications for medical education reform. Providing formal training to geriatric medical educators on how to teach clinical reasoning—particularly in the context of diagnosing older adults—may contribute to improved diagnostic accuracy and patient outcomes. Future directions include developing workshops and other educational modalities to “teach the teachers.”

References

- Burgener AM. Enhancing communication to improve patient safety and to increase patient satisfaction. Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2020;39(3):128–132.

- Cassel C, Fulmer T. Achieving diagnostic excellence for older patients. JAMA. 2022;327(10):919–920. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.1813

- Santell JP, Hicks RW. Medication errors involving geriatric patients. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31(4):233–238. doi:10.1016/S1553-7250(05)31030-0

- Skinner TR, Scott IA, Martin JH. Diagnostic errors in older patients: a systematic review of incidence and potential causes in seven prevalent diseases. Int J Gen Med. 2016;9:137–146. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S96741

- US Census Bureau. 2020 Census Data. Accessed [Month Day, Year]. https://www.census.gov

- Durning SJ, Jung E, Kim DH, Lee YM. Teaching clinical reasoning: principles from the literature to help improve instruction from the classroom to the bedside. Korean J Med Educ. 2024;36(2):145–155. doi:10.3946/kjme.2024.292

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Core Elements of Hospital Diagnostic Excellence (DxEx). Accessed [Month Day, Year]. https://www.cdc.gov/patient-safety/hcp/hospital-dx-excellence/index.html

- Mohd Tambeh SN, Yaman MN. Clinical reasoning training sessions for health educators: a scoping review. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2023;18(6):1480–1492. doi:10.1016/j.jtumed.2023.06.002

- Wagner F, Sudacka M, Kononowicz A, et al. Current status and ongoing needs for the teaching and assessment of clinical reasoning: an international mixed-methods study from the students’ and teachers’ perspective. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24:622. doi:10.1186/s12909-024-05518-8

- Gold JG, Knight CL, Christner JG, Mooney CE, Manthey DE, Lang VJ. Clinical reasoning education in the clerkship years: a cross-disciplinary national needs assessment. PLoS One. 2022;17(8):e0273250. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0273250