Other Publications

Education Columns

A Process for Addressing Burnout in an Academic Department: Adapting the LISTEN SORT EMPOWER Model

By Jessica L. Jones, MD, MSPH; Katherine Fortenberry, PhD; Sundy Watanabe, PhD; Darin Ryujin, MS, MPAS; University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT

Health care professional burnout has increased since the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies emphasize the importance of implementing interventions to promote wellness.¹ Assessing burnout is important to determine the need for intervention. However, burnout and workplace satisfaction are multifaceted.² Identifying interventions to improve well-being and effect change at an institutional level can be challenging. The American Medical Association (AMA) endorses the iterative, team-centered LISTEN–SORT–EMPOWER (LSE) model to identify, assess, and eliminate sources of burnout. The LSE process calls for organizations to (1) identify challenges in the workplace through directed conversations, (2) evaluate and prioritize opportunities for improvement, and (3) make changes to resolve problems.³

As originally described, the LSE model was aimed at improving burnout in clinical settings, typically consisting of relatively small and cohesive groups of individuals. This narrative describes the use of the LSE model to clarify satisfaction assessments, identify areas of concern, and develop a plan to improve the culture of a large academic department. This department includes 4 separate divisions with overlapping but distinct research, educational, and clinical missions, which lead to disparate needs and priorities. This narrative outlines the use of surveys and focus groups to LISTEN, followed by small interactive sessions to SORT and EMPOWER.

Listen

The Listen process involves identifying sources of benefit and concern in a safe space. We used employee satisfaction surveys and focus groups to clarify the survey results. Focus group data were collected and analyzed by an external expert consultant. A focus group report was disseminated to all personnel. An anonymous, open-ended follow-up survey was also conducted for faculty to clarify items from the satisfaction survey. An informal meeting was held to allow staff to comment on the results. This multistep approach to listening was intended to balance confidentiality and broad representation while allowing a deep dive into specific concerns via focus groups.

Sort and Empower

The Sort process categorizes the sources of concern into opportunities for improvement prioritized by impact and feasibility. The outcome of this process is a ranked list of opportunities that a team has the control and resources to address. The goals of the Empower process are to use the highest-ranked opportunities for improvement to develop solutions to improve the workplace and to leverage the support of appropriate administrative leaders.

At our institution, equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) and wellness leaders hosted 6 virtual meetings to prioritize the themes elucidated from the focus groups and satisfaction follow-up survey. After prioritizing themes (Sort), we developed recommendations to improve our work environment (Empower).

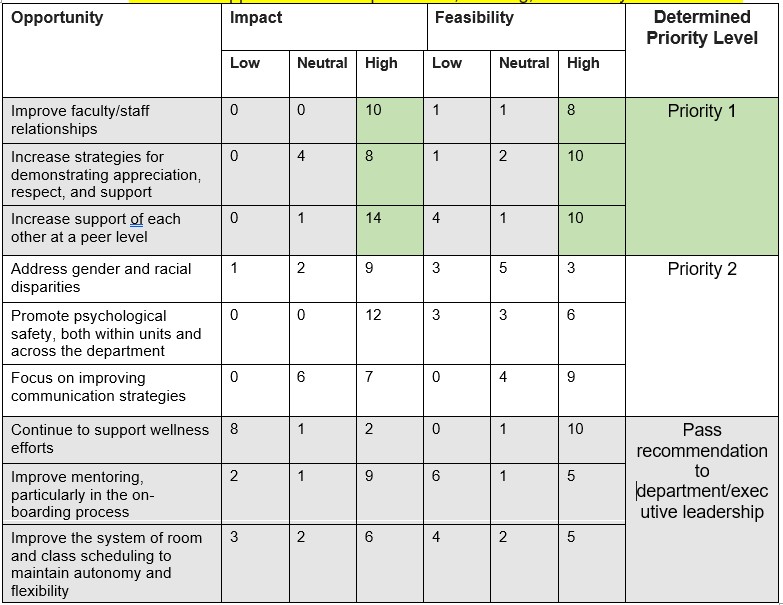

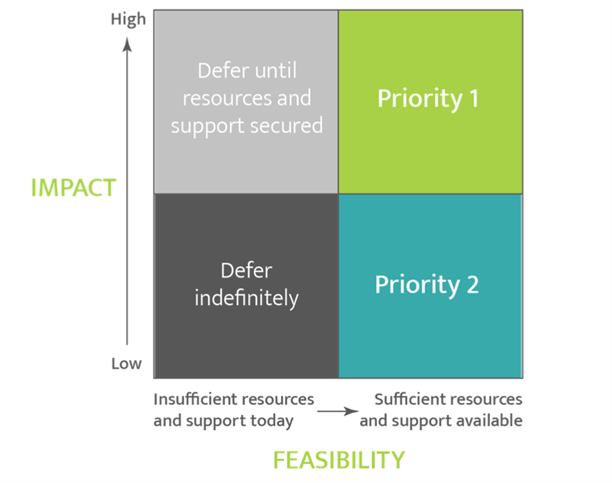

During 2 Sort sessions, participants used 2 × 2 tables for each theme (opportunity for improvement) identified through the Listen process, with the y-axis representing impact and the x-axis feasibility (Figure 1). Opportunities with the highest number of marks in the high-impact and high-feasibility sections were designated top priority (Table 1).

Table 1: Identified Opportunities for Improvement, Ranking, and Priority Determination

Figure 1

Figure Legend

Figure 1: Example of Table used during the Sort process.4 2x2 table utilized to categorize impact and feasibility, then determine priority for each opportunity for improvement. The y-axis of the table represented perceived level of impact, and the x-axis represented the perceived level of feasibility for implementing change

During 4 Empower sessions, we divided participants into 3 working groups. Participants anonymously typed comments onto an online whiteboard website using their personal computers. Leaders reviewed and summarized the comments for each of the working groups into possible action items and recommendations for leadership (Table 2). During subsequent Empower sessions, the working groups framed the recommendations into actionable items for implementation. Both the Sort and Empower sessions were designed to encourage broad input by allowing both discussion and anonymous comments.

Table 2: Opportunities for Improvement and Team-Informed Recommendations for Change in the Workplace

Broader Implications

Use of the LSE process can be replicated and adapted to improve a range of workplace environments. The Stanford Model of Professional Fulfillment recognizes that a culture of wellness in the workplace requires regular assessment, commitment and support from key stakeholders, and demonstration of appreciation.⁴ The effort described here includes several of these factors for success.

It is critical that an EDI perspective be prioritized when developing and implementing well-being interventions, as individuals from underrepresented backgrounds often experience greater barriers and lower psychological safety when expressing their well-being needs. Enabling all participants to provide input, particularly those whose voices might otherwise be silenced or minimized, is essential.⁵⁻⁶ We recommend including experts in both well-being and EDI when using the LSE model.

Improving well-being in health care organizations is a critical need, complicated by multiple barriers. Identifying actionable interventions can be difficult. However, use of the LSE model can promote success by ensuring that interventions are driven by the voices of the individuals they will impact. We hope that other organizations might consider this process as a baseline for improving well-being in their environments.

Acknowledgements:

Special thanks to the staff personnel who facilitated the logistics of this work, and to the department executive committee for their continued support for this effort.

References

- Medeiros KS, Ferreira de Paiva LM, Macedo LTA, et al. Prevalence of burnout syndrome and other psychiatric disorders among health professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. PLoS One. 2021;16(12):e0260410. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0260410

- Stepanek M, Jahanshahi K, Millard F. Individual, workplace, and combined effects modeling of employee productivity loss. J Occup Environ Med. 2019;61(6):469-478. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001573

- Swensen SJ. LISTEN–SORT–EMPOWER: Find and act on local opportunities for improvement to create your ideal practice. AMA STEPS Forward. American Medical Association. Accessed September 9, 2025. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2767765

- Stanford Medicine. The Stanford Model of Professional Fulfillment. Stanford University. Accessed September 9, 2025. https://wellmd.stanford.edu/about/model-external.html

- Swensen S, Kabcenell A, Shanafelt T. Physician-organization collaboration reduces physician burnout and promotes engagement: the Mayo Clinic experience. J Healthc Manag. 2016;61(2):105-127. doi:10.1097/00115514-201603000-00008

- Swensen SJ, Shanafelt T. An organizational framework to reduce professional burnout and bring back joy in practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43(6):308-313. doi:10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.01.007