Using Video-Assisted, Workshop-Style Teaching to Improve Medical Students’ Knowledge and Confidence in Suturing

by Sumira Koirala, MD; Michael Paronish, MD; Thomas Macabobby, MD; Lisa Weiss, MD; Shawna Koprucki, MD; St. Elizabeth Boardman Family Medicine Residency, Boardman, OH

Background

The Association of American Medical Colleges recognizes suturing as one of the essential procedural skills that medical students must be able to perform upon graduation.1,2 Suturing is an important technique that allows optimal wound healing of skin incisions and lacerations.3 However, there is a lack of standardized curriculum for suturing, and students frequently feel unprepared to practice this skill when they enter higher levels of training.2 Studies have shown that students who practice with video instructions have substantial improvements in procedural skills in comparison to students who receive traditional instructor feedback alone.4,5 We have implemented a suturing workshop for our medical students that combines both the supplemental videos and instructions from faculty. The goals of the workshop are to increase the knowledge and skills in suturing and to create more confidence to perform these procedures.

Implementation

The third- and fourth-year medical students who rotate at the two Youngstown, Ohio-area Bon Secours Mercy Health Family Medicine Residency Programs participate in a 90-minute suturing workshop led by a family medicine residency faculty. The students receive a brief, interactive lecture on aspects of suturing, including types of suturing materials, suturing techniques and their indications, instruments used for suturing, and complications of poor surgical techniques. After this lecture, students watch instructional videos on instrumentation tie and multiple suture types: simple interrupted, simple buried, vertical mattress, horizontal mattress, figure of eight, half buried, simple running, simple running locking, and subcuticular running sutures. The video is paused after each technique, and the students start practicing on silicon suture pads while the faculty physician walks among the students to offer feedback and instructions.

Methods for Measuring Outcomes

We surveyed 56 medical students who rotated between September 2020 and December 2021 before participating in the workshop. They were asked to rate their suturing skills and their confidence to perform suturing. They were also surveyed postworkshop to assess their perception of improvement in their skills and confidence to perform suturing. We used anonymous paper questionnaires using confidence ratings for the survey; 56 students participated in this study (100% response rate).

Results

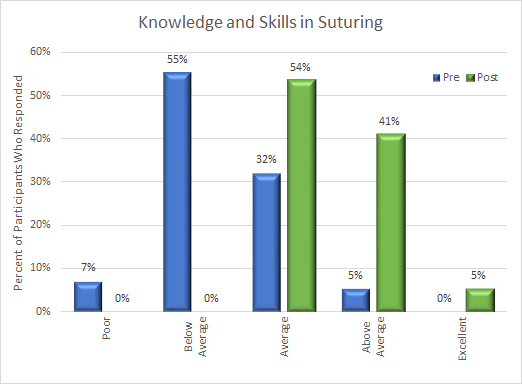

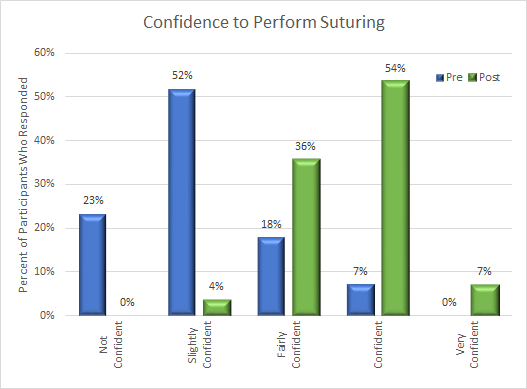

The results of the survey are shown in Figures 1 and 2. Most medical students reported that they had below-average skills and low confidence to perform suturing. After participating in the workshop, students felt that their skills and confidence to perform suturing improved.

Figure 1

Figure 2: Confidence to Perform Suturing

Discussion

Suturing skills are integral to the practice of comprehensive family medicine. Our study demonstrated that students recognize the importance of suturing skills. This workshop-style teaching session utilizing instructional videos and faculty instruction provided meaningful improvement on acquisition of suturing skills and enhanced confidence to perform these techniques. This curriculum is reproducible and provides a high level of consistency of experience for learners. Students improving skills as well as perception of their skills will likely lead to increased competence in the procedural domains and have them better prepared for their future educational pursuits. The familiarity will serve them well in other rotations and as they enter residency. Including procedural training sessions like these during medical school rotations will expose students to the hands-on side of family medicine. Future investigations to demonstrate the effectiveness of the teaching technique could be conducted by using observed ratings by faculty.

References

- AAMC Medical School Objectives Writing Group. Learning objectives for medical student education—guidelines for medical schools: report I of the Medical School Objectives Project. Acad Med. 1999;74(1):13-18. doi:10.1097/00001888-199901000-00010

- Dehmer JJ, Amos KD, Farrell TM, Meyer AA, Newton WP, Meyers MO. Competence and confidence with basic procedural skills: the experience and opinions of fourth-year medical students at a single institution. Acad Med. 2013;88(5):682-687. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828b0007

- Khan MS, Bann SD, Darzi A, Butler PE. Assessing surgical skill. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(7):1886-1889. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000091244.89368.3B

- Summers AN, Rinehart GC, Simpson D, Redlich PN. Acquisition of surgical skills: a randomized trial of didactic, videotape, and computer-based training. Surgery. 1999;126(2):330-336. doi:10.1016/S0039-6060(99)70173-X

- Shippey SH, Chen TL, Chou B, Knoepp LR, Bowen CW, Handa VL. Teaching subcuticular suturing to medical students: video versus expert instructor feedback. J Surg Educ. 2011;68(5):397-402. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2011.04.006