Other Publications

Education Columns

All “Feedback” Is Not the Same: Use Correction, Criticism, Feedback, Feedforward, and Grades at the Appropriate Time

By Allen F. Shaughnessy, PharmD, MmedEd, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA; Christopher A. Shaughnessy, BA, Boston, MA

All of us have given and received feedback; some of it has been helpful, some harmful, some both. The best feedback provides actionable information to the receiver that is specific, judgment free, and does not induce guilt or shame.

To help improve feedback in our residency, we have developed a rubric that acknowledges that all feedback is not the same but varies on when it is given relative to the observed behavior and also depends on the number of observations. We teach the principles and framework of nonviolent communication, a philosophy and style of communication designed to increase empathy and improve the quality of life of both those who use the method as well as the people around them. The method uses this format: "When you [behavior], I feel [honest feeling]. I need [need not being met]. Please [request for behavior]".1 Residents use this framework when developing group feedback to preceptors and we have used it to identify, from their perspective, teaching best practices.2 Faculty members, through faculty development, learn to use the format when providing feedback to residents. In a series of 13 semi-structured interviews with preceptors, all but one were appreciative of the feedback style and respected the process, even if they didn’t agree with the feedback itself. Some preceptors could recall very specific feedback given several years before in this format and could explain how they used the feedback to change their teaching.

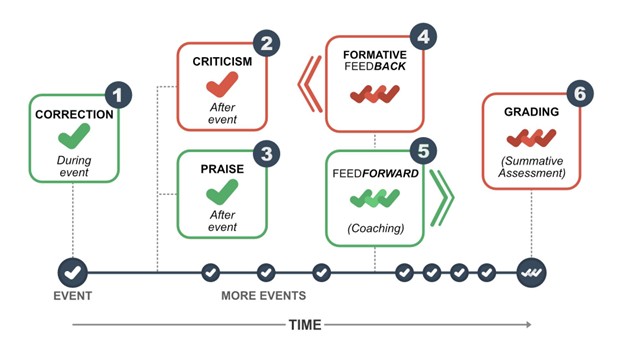

Figure 1:

However, not all “feedback” is the same and therefore the reaction to it depends on timing of its delivery, the extent of observation on which the feedback is based, and the intent of the giver. Selecting the right type of feedback depends on all three factors (Figure 1):

1) Correction is given in the moment about a specific event when the receiver can immediately react and change their behavior. It is short, declarative, and behavior-specific, based on a single observation. "Move your hand here," or "Please speak louder to the group" are examples.

2) Criticism is feedback also offered after a single event when the receiver cannot change behavior. As a result it is frequently not helpful. “Your hand was in the wrong position during the procedure,” or "Your voice was too soft during your presentation" are examples.

3) Praise of a specific behavior, given after a single event can be helpful to develop a learner’s confidence and reinforce the behavior. “The tone of your voice was just right” is behavior-specific praise. However, a general evaluation – “Good job”– may leave learners unclear as to what action they performed well.

4) Formative Feedback is often given to help a learner progress toward a goal, it is firmly rooted in observation of a series of past behaviors. It is limited and static, e.g., “You spend more time with your very first patient than your subsequent patients during a patient care session.” This type of feedback often generates justification and defensiveness.

5) Feedforward (coaching) is advice that receivers can use to change behavior in the future.3 Its aim is to help learners do something right rather than to prove they were wrong. It can cause less defensiveness because it is more trustworthy and conveys an intention to help: “Here’s an idea for you.”4 Offering feedforward advice typically is faster and more efficient than feedback because time is not spent deconstructing past behavior. It starts with the observed behaviors and offers solutions for the future: “I notice you often speak softly; in the future you might want to try to project more.”

6) Grading (summative assessment) is a final judgment or ranking given at a time when future action cannot be performed (except, when the grade is not satisfactory, starting the learning over again). Grades, while useful for ranking learners or determining whether minimum criteria are met, do not enhance learning after they are rendered.

Another crucial aspect of helping learners to grow is the intent of the giver. The Buddhist concept of “right speech” suggests that feedback can either be given as a form of compassion and generosity to help the receiver or as a means of expressing aversion or indignation to meet our own needs.5

We need to examine our intentions to determine whether the feedback we intend to give is about us or the receiver. Feedback is about us if it is based on our impatience, biases, right-and-wrong judgments, the desire to demonstrate our knowledge, intellect, or superiority, or the desire to be right. If, however, it comes from a place of sincerely trying to help the learner improve, it is about them. Examining our motives, especially when giving feedback from a place of power, is essential.

We all have instances of where we have received feedback that has caused us psychological distress. At best, feedback can be helpful and generative; at worst it can cause avoidable harm.

References

- Rosenberg MB. Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life: Empathy, Collaboration, Authenticity, Freedom. 3rd edition. PuddleDancer Press; 2015.

- Shaughnessy A, Sokol R, Fleishman J, Wahid O. What Do Residents Want From Preceptors? A Study of Feedback Generated by Family Medicine Residents. Ann Fam Med. 2024;22(Suppl 1):6255. doi:10.1370/afm.22.s1.6255

- Goldsmith M. Feedforward. Writers of the Round Table Press. 2012

- Milyavsky M, Gvili Y. Advice Taking vs. Combining Opinions: Framing Social Information as Advice Increases Source’s Perceived Helping Intentions, Trust, and Influence. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2024;183:104328. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2024.104328

- Bamford, G. (2014), "Right Speech as a Basis for Management Training", Journal of Management Development, Vol. 33 No. 8/9, pp. 776-785. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-09-2013-01225.