The Student-Run Clinic: A Setting for Team-Based Interprofessional Education

Wendy C. Hsiao (Keck School of Medicine), Kathleen N. Beasley (School of Pharmacy), Mia Mackowski (School of Pharmacy) Joo-Hye Lee (School of Pharmacy) Natasha Germain (Keck School of Medicine, Division of Physician Assistant Studies), Diana Jin (Keck School of Medicine) Solange Ku (Mrs T.H. Chan Division of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy), Christopher P. Forest (Keck School of Medicine, Division of Physician Assistant Studies), Brian Prestwich (Keck School of Medicine), University of Southern California.

The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model is increasingly recognized as a method to accomplish the “Triple Aim” of improving patient care processes, clinical outcomes, and lowering or stabilizing health care costs.1,2 Key to the PCMH is the concept that interdisciplinary team-based care can comprehensively address patient needs.3 As acceptance of the PCMH increases,4 academic institutions prepare future health care providers via interprofessional education (IPE): persons from two or more professions learning with, from, and about each other in order to achieve better patient outcomes.5,6 We propose an interprofessional, student-run primary care clinic as an ideal setting for IPE, using our institution’s novel student-run clinic (SRC) as an example.

SRC Overview

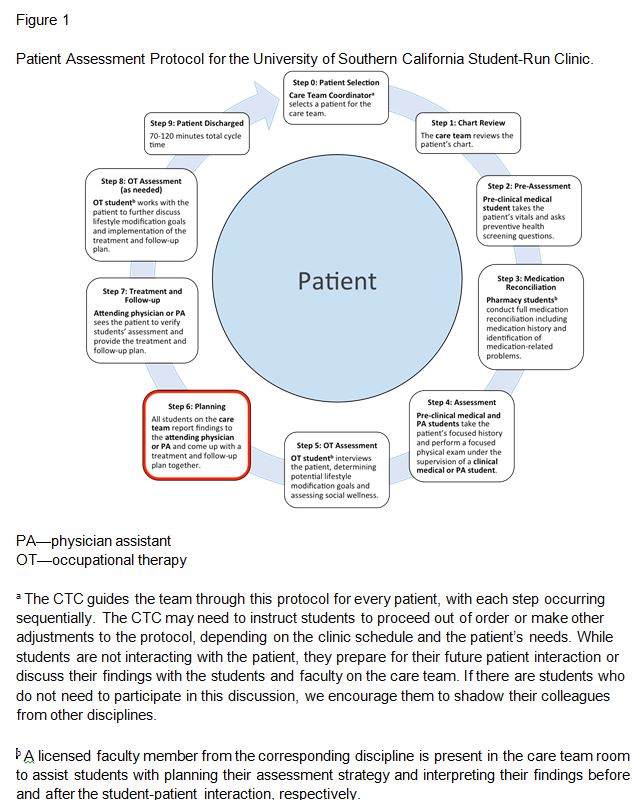

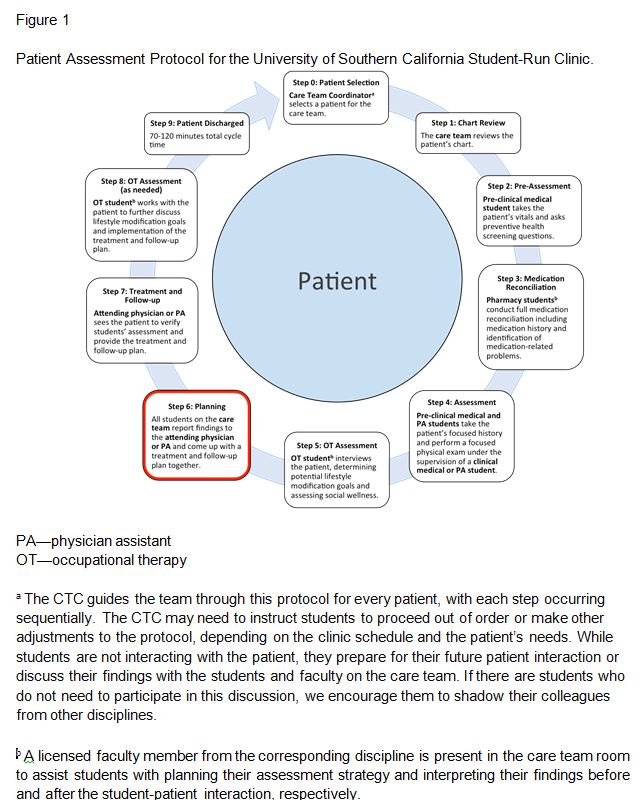

Our SRC is a collaboration between our institution’s medicine, physician assistant (PA), pharmacy, and occupational therapy (OT) programs, in cooperation with two Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs). Student involvement is voluntary, and approximately 20%, 40%, 15%, and 15% of our institution’s medical, PA, pharmacy, and OT students participate, respectively. Students care for underserved urban patient populations ranging from the working poor to the homeless, many of whom have complex health and socioeconomic issues that may ideally be addressed by an interdisciplinary primary care team. Under faculty supervision, students work in interprofessional care teams to provide patients with a comprehensive history and physical exam, preventative screenings, behavioral counseling, medication reconciliation, and wellness/lifestyle modification education. Notably, students from every profession participate in the assessment and treatment planning for all patients (Figure 1). In addition, as the attending providers are employees of the FQHCs, the FQHCs can be reimbursed for SRC services, substantially minimizing operating costs for our SRC and institution.

The SRC runs on select Saturday mornings at the FQHCs, with two to three care teams operating per day. Each team examines one to four patients with an ideal cycle time of 70–120 minutes per patient, depending on the complexity of the patient’s needs. The care team consists of one care team coordinator (CTC), two preclinical medical students, two pharmacy students, one preclinical PA student, one clinical medical or PA student, one OT student, one attending physician or PA, one pharmacist, and one OT. The CTC, a student from any participating profession, is responsible for orienting students, managing time, delegating tasks, and facilitating communication. SRC student leaders train volunteers on the patient assessment protocol (Figure 1) prior to the volunteers’ attendance, and students perform appropriate assessments and reporting according to their program’s curriculum. As the protocol advances, each care team member verbally informs the next team member of any relevant findings before the team member proceeds. When students are not interacting directly with the patient, faculty or the CTC encourage them to explore topics such as concepts related to the patient’s care or the scopes of practice of each of their respective professions.

Conclusion

Unlike most interdisciplinary SRCs that run parallel services, our SRC fully integrates the unique skills and knowledge base of the four professions for every patient while encouraging communication and teamwork. Limitations in implementing the protocol outside of academia may include provider reimbursement issues. Patients also may become frustrated at the amount of time spent at the clinic, though clinic providers who then see these patients in continuity are able to serve them thoroughly due to the extensive database provided by the SRC. We believe that our model is a worthy IPE experience while optimizing three of the pillars of primary care—patient access, comprehensive care, and coordinated care. Through interdisciplinary student-student/faculty-student teaching, tangible clinical experiences, and integration into established community health clinics, our SRC educates students beyond the traditional curriculum to better prepare them to address our nation’s growing health care needs.

Acknowledgements: The University of Southern California Student-Run Clinic is made possible through the support of the Medicine, PA, Pharmacy, and OT programs at the University of Southern California, the USC-Eisner Family Medicine Center at California Hospital, and the John Wesley Community Health Institute Center for Community Health Downtown Los Angeles.

References

- Starfield B. Primary care: balancing health needs, services, and technology, revised edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Institute for Health Care Improvement. The Triple Aim. http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/pages/default.aspx. Accessed March 19, 2015.

- Reynolds PP, Klink K, Gilman S, et al. The patient-centered medical home: preparation of the workforce, more questions than answers. J Gen Intern Med 2015 Feb 24. [Epub ahead of print]

- Takach M. About half of the states are implementing patient-centered medical homes for their Medicaid populations. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012 Nov;31(11):2432-40.

- Bridges DR, Davidson RA, Odegard PS, Maki IV, Tomkowiak J. Interprofessional collaboration: three best practice models of interprofessional education. Med Educ Online 2011 Apr 8;16.

- World Health Organization. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2010/WHO_HRH_HPN_10.3_eng.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2015.